The Story of Two Cousins and The Kamiriithu Theatre Movement

The Kamiriithu Cultural Center was a community-based theatre movement in Kenya. Its genesis can be traced back to an ingenious approach of resistance against imperialism. Its magnetism and camaraderie were reminiscent of the famed Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s. Throughout the period, para-dramatic theatre forms which deviated from conventional dramatic structures played a pivotal role in fostering African unity against their British oppressor. Other theatrical uprisings preceded the movement. Noteworthy among these are the Gicamu theatre movement endorsed by the praised freedom fighter Dedan Kimathi at Karura-ini in Nyeri and the University of Kenya’s Travelling Theatre. In his book ‘African Popular Theatre’ David Kerr writes that what set Kamiriithu apart was that the initiative for community revival emerged from the grassroots. It came from the people themselves. Its steering committee was not led by bourgeois African elites, but rather, by a group of mere peasants and workers from the village. Together, they rehabilitated the community centre in 1976, one which had been neglected three years prior. Thence the Kamariithu Community Educational and Cultural Centre (KCECC) was born.

Of immediate concern to the management committee was the illiteracy levels that ran deep and wide within the local community. In an effort to alleviate this situation and engage the newly literate peasants, the sub-committees in charge of literacy and culture recruited Ngugi wa Mirii and cousin Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Now, I know you might be wondering whether this may be Ngugi wa Thiong’o the reknown. The answer is Yes. The two were commissioned to develop a play script derived from personal accounts authored by these recently literate villagers. By June 1977, the renowned play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want) had been drafted. Ngugi wa Thiong’o attests in his book ‘Detained’ to having witnessed peasants, many of whom had never experienced theatre before, conceptualize and construct an open-air theatre featuring a raised stage, and an auditorium of semi-circularly raked seating that somehow resembled a Greek amphitheatre, and whose capacity could accommodate over two thousand people. The play was performed for weeks on end. So moved and captivated were the neighbouring villagers, that they too made preparations to build their own theatres and community centres, hence the Kamiriithu Theatre Movement. The words “Mucii wa Muingi” (The People’s Cultural Centre) were inscribed over the entranceway.

Made by Africans, Watched by the World

I believe it is Albert Einstein that commented “If you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing it is stupid”.

It goes without saying that storytelling was the Kamiriithu Theatre Movement’s tool of trade. Just as so, Kenyans, and Africans at large take to storytelling like fish to water. In a bid to participate in the revitalization of the region’s creative economy (whilst making money doing it) Netflix disrupted the industry with a campaign tagged #AfricaOnNetflix. The campaign was an exciting invitation to Africa from the international community to showcase her honed ability to tell compelling stories, and for the rest of the world to give them a listen. To this end, Africa’s debut on Netflix’s global streaming platform was commemorated by a grandiose video commercial that is best likened to Jesus’ triumphant entry to Jerusalem. It was dubbed Made by Africans, Watched by the World. How very grand!

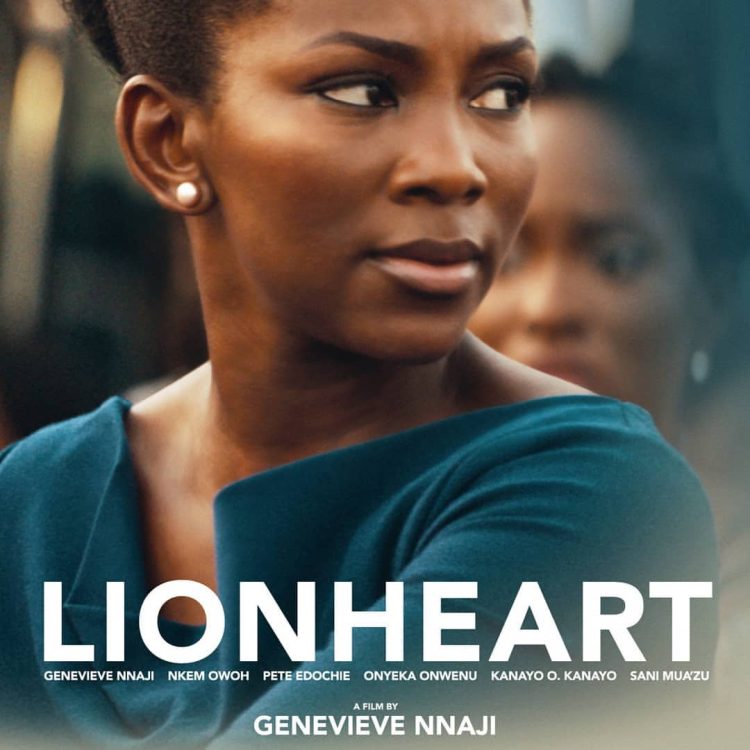

Of the Lion’s Heart and Daisy’s Sincerity

As the first African cinema to premiere on Netflix, Lionheart, a Nollywood production, paved the way, breaking the ice for other African films. In a similar vein, Sincerely Daisy accomplished a comparable feat, serving as a trailblazer for Kenya’s film industry on the streaming platform.

Enter Stage… Kenya

Just this once, allow me to call a spade a big spoon – and somewhat – dance around an unspoken actuality. I thoroughly enjoy Kenyan screenplays and watch them religiously so. Be this as it may, I must confess that some of them do not particularly resonate with me. Unbeknownst to many- astonishingly so Kenyans as well – Kenya boasts a rich assortment of riveting films besides the commonplace that is Nairobi Half Life. Whether to attribute this to marketing that falls short of the respective films’ glory, distribution channels being out of the larger audiences’ reach, or whatever else one could concoct is not a question to be answered in this article, but perhaps in another. Granted, Nairobi Half Life is an indisputable Kenyan classic whose reverence must be expressed. The devil’s dues must always be paid. Having that said, there still exist alternative selections available that are equally exceptional in both quality and impact. Pictures you might take a liking to. Those that when you consume, (assuming you are Kenyan), you will fancy them a good watch, as opposed to bearing with them purely out of duty to your nation.

Below are the writer’s picks which, patriotism aside, I find worth the binge:

Should you opt to overlook the subsequent recommendations, I implore you to give Lusala a try. The most befitting phrase that captures the film’s feel would be “You’ll never see it coming”. Because trust me, you won’t. The star-studded screenplay unfolds in presumable mundanity at first, only to take a dark, unforeseeable turn: a plot twist that commands applause, even that of deity. The selling point for this film has to be its script. The 1h long drama is the brainchild of minds I consider nothing short of genius. The playwrights, Silas Miami, Wanjeri Gakuru and Oprah Oyugi are deserving of a standing ovation.

The script is hinted with dots one can only join backwards. The subject matters tackled are relevant, necessary and well put. They go about topics that are otherwise: ill-represented, not-talked-about-enough, and a notorious cause for stigmatization: with so much grace and valour. The piece lifts the rug that society often sweeps its dirt under in such a tasteful and artistic manner.

The lead actors, Brian Ogola, playing Lusala and Stycie Waweru, playing Bakhita; commendably embody their characters in full. So much so, that you can barely tell them apart. Finally, it is imperative to give Mugambi Nthiga his flowers on this film as his directorial debut, a significant milestone in his career. A true work of art.

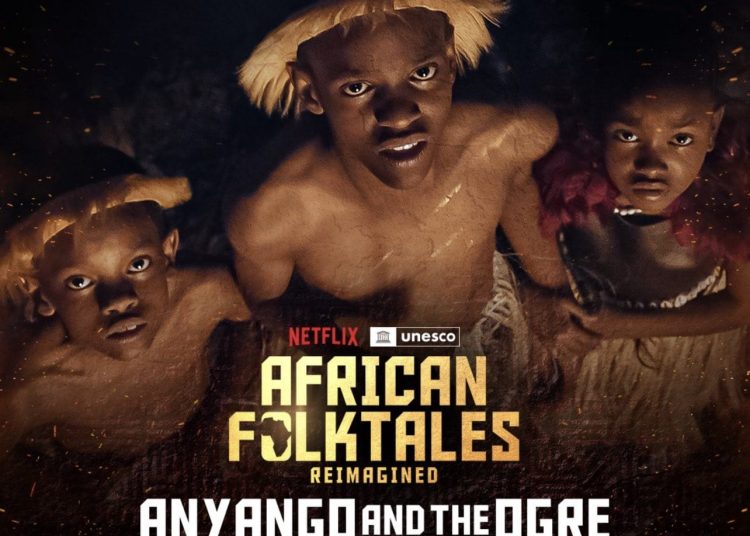

2. Anyango and the Ogre – African Folktales Reimagined

In what can be described as a measure of the current generation’s mastery of the folktales hitherto passed down, African creatives pay homage to their roots in a manner befitting the present times, a Netflix reboot. ‘African Folktales Reimagined’ is a contemporary anthological rendition of six oral traditions inherited from our ancestors across Africa. As is any adaptation, the basic plot remains intact with tweaks done to enhance its delivery, either in part or in whole.

Anyango and the Ogre is a folktale all too familiar to the Dholuo tribesmen. Its reenactment via an audiovisual medium not only gives it a new lease of life but also disallows it from succumbing to the eroding effects of time, as has befallen numerous other African oral traditions. Written by the phenomenally talented writer Violine Ogutu, who many know from her work on 40 Sticks (2020), How to Find a Husband (2015), Waliobaki (2016) and more recently, the recently premiered Netflix original series Supa Team 4. Starring Kenya’s household name, Sarah Hassan- who is just as good a producer as she is an actress in the reimagined piece – and the impressionable boy actor, Trevor Jones Kamau – whose debut on the silver screen comes across as organic.

The synopsis of Anyango and the Ogre stands out for its superiority. Its blueprint draws on a skilful juxtaposition between two African settings – a native realm and a futuristic backdrop. This interplay of parallels converges more than it contracts, creating a harmonious work of art. Also worth mentioning is its overall production and execution. Suffice to say, the depiction of tech motifs in African films is sometimes subpar. This can, to some extent, be attributed to insufficient expertise and, to an even greater extent, the constraints of tight budgets. This often leaves the end product feeling tacky and lacking the desired polish. Anyango and the Ogre takes on the daring move to embrace tech motifs in its production and executes it with exceptional precision.

Anyango and the Ogre can be enjoyed by adults and children alike. I dare say, adults may even find it even more entertaining than the intended target audience, the children themselves. The 18min long film is truly one worth writing home about.

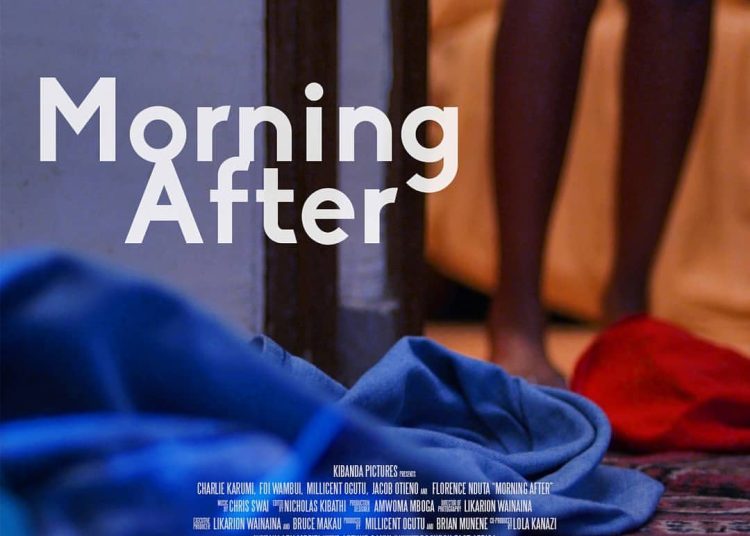

Morning After is a 13min short comical skit that exemplifies Murphy’s Law, anything that can go wrong will go wrong, or as the Swahili put it, Siku ya nyani kufa, miti yote huteleza (On the day of the monkey’s passing, all trees will be slippery). It is a light watch narrating the misfortunes that befall Joe on the morning following his excessive overnight escapades. Played by Charlie Karume, Joe’s boyish persona cheekily attempts to navigate a sticky situation with his one-night stand, played by Foi Wambui, and his deadpan Christian roommate. The production is written and directed by the renowned Brian Munene who, through this film, continues to assert his superiority in the film industry alongside his close friend and colleague, Likarion Wainaina.

In a fashion typical to international African depiction in film, Country Queen makes its grand entrance in this list. The film edges its place as the inaugural Kenyan drama series on Netflix with a screenplay all too familiar to that of the African context, particularly so Kenya’s own. Like many films hitherto contextualized in Africa;

(Hitherto… Love that word:)

it sketches its broadest outline around the complex relationship Africans have with Africa’s goodies, her minerals. Africa’s mineral endowment has been known to be so much so her greatest blessing, as it is her curse. This film gives life to the contentious commercial proclivities that have plagued the continent as a result of its endowment. It artistically explores how these resources, particularly in the context of gold mining, lead to complex and often exploitative dynamics, whose brunt local communities bear, painfully so. The drama series is six episodes heavy, each running an average of an hour.

A multitude of subject matters are brought forth in this mostly Afro-Rural film. The contemporary relevance of these demands a separate article, hence, will be discussed at length in the next. Nonetheless, I believe this drama series to be an episode-turner.

5. The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind

Okay. You caught me. I might have stretched the truth on this one. The boy who harnessed the wind is not solely Kenyan. It is a pan-African production. I opted it in as it boasts an extensive roster of Kenyan actors – both A-listers and fresh faces – all of whose performances are worth writing home about. The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind is a film based on the real-life events of one William Kamkwamba, a story so compelling that even the printing press found it worthy of its penmanship. The film peddles hope to the masses, notably so to the rural African child. The film is set in Malawi and predicates a rural town centre enduring the harsh impact of climate change on its crop. Inextricably intertwined are other equally plausible abstractions whose duplicity to other African counties is apparent.

The Pan-African film featured commendable acting from its cast. In this piece, I will mention by name Kenyan actors whose performances I am proud to associate with my motherland, Kenya. Maxwell Simba, whose film lead debut, everyone followed. The famous actor Raymond Ofula, whose voice should be earmarked in the pages of Kenya’s history as a national treasure. Robert Agengo who, prior to the film, I had only seen in Citizen Tv’s Zora as the homme fatale and the lead antagonist in 40sticks. Martin Githinji (aka Daddie Marto), popularly known for his role in Sue na Jonnie, whose part in the film though brief, was played well. Lastly, Melvin Alusa, a familiar face to this list (Country Queen’s lead actor).

Shalom Kendi Mbae

A Writer. A Pan-African. A Conversationalist.

Words are to me what numbers are to a mathematician.

This little light of mine, I'm going to let it shine.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Well done daughter. Happy to celebrate your good work. May the lord bless you, increase you, empower you and open the floodgates of heaven. May the blessings flow and overtake you in Jesus name.