If I had to choose one word to describe Kenya, it would be ‘diversity’. Kenya is truly a diverse country. Whether philosophically, culturally, or linguistically. With more than 42 tribes, all originating from various parts of the African continent throughout the course of history, every part of Kenya is essentially a unique cultural spot on its own. Because of this diversity, a special intersection of talents feeds into the Kenyan music scene to keep Kenyans and the world at large inspired, educated, and entertained. Music lovers in Kenya can bob their heads to Benga, Hip-hop, Reggae, Afrobeat, Gengetone, Kapuka, Genge, and folk music in over 40 national languages.

Kenyan music has come a long way with a rich history that spans decades and encompasses a diverse range of styles and genres. From the measured rhythms of Benga to the urban youth sounds of gengetone, Kenyan music has evolved significantly over the years, reflecting the changing tastes and cultural influences of the country’s young and vibrant population. In this post, we take a closer look at the different styles of Kenyan music, exploring their origins, key characteristics, and notable artists.

Along the way, we also delve into the social and cultural contexts that have shaped the evolution of these styles, offering insight into the unique sounds and influences that have contributed to the growth and popularity of Kenyan music around the world. Whether you’re a fan of Benga, Afrobeat, Folk Music, Taarab, or the more contemporary sounds of Gengetone, this guide will give you a better understanding of the diverse range of styles that make up Kenyan music and the cultural forces that have shaped their development.

Precolonial Kenya

Music was an important part of the culture of native Kenyans. Music was a communal affair, with people coming together to sing and dance at weddings, initiations, funerals, and other ceremonies. Music played a central role in the spiritual and social life of the community. When we talk about “native” music and dance in Kenya, we refer to the cultural practices and expressions that were passed down within various communities in Kenya for generations before colonialism. These forms of artistic expression reflected the history, values, and beliefs of various Kenyan communities that existed at the time, and played a significant role in preserving and promoting the unique cultural identities of these communities.

However, despite their importance, archives on native Kenyan music are scarce and neglected. Information about music in precolonial Kenya is gathered from personal anecdotes of old Kenyans concerning music events of their time, colonial archives of minutes and orders and in few cases, correspondence between administrators and other actors involved during the colonial occupation of Kenya (missionaries and settlers). In many cases we lack adequate documentation and resources to learn about and appreciate the history of Kenyan music, putting these forms of cultural practice at risk of being lost or forgotten over time as Kenyans from older generations age and pass away, taking their cultural knowledge with them. This is a huge problem because native Kenyan music plays a vital role in the cultural fabric of our country, and their preservation is crucial for the continued vitality of our cultural practices.

Colonial Kenya

During the colonial occupation of Kenya that lasted from 1885 to 1963, references to music practices were scarce and racially biased. Colonial administrators, missionaries and scientific observers all approached Kenyan music and Kenyan culture in extension through racially prejudiced lenses. It is no surprise then that in a gazette report made in 1936, the following is written: “There is little to say regarding Turkana dances as they consist almost entirely of a large number of men walking about, stamping their feet.” In his book ‘THE AKIKUYU (Kikuyu) – Their Customs Traditions and Folklore‘ the missionary Cagnolo remarked “Music amongst civilized nations represents the soul of a people but with the Akikuyu it expresses merely their present feelings.” Judgment was passed swiftly condemning most native cultural practices while the rest was reduced to irrelevant entertainment.

Local dance and music events became fewer by the day as they continued being suppressed and prohibited. Festive gatherings, ceremonies and initiation rituals were highly regulated, requiring permits since they were considered dangerous agitation mediums conducive for riots. To the colonial administration, the control and regulation of music and dance practices was viewed as necessary for successful governance.

Post-Independence Kenya

Kenya’s independence in 1963 catapulted Nairobi, Kenya’s capital city, into a crucial commercial center in East Africa. The next two decades following independence marked an innovative and exciting time in Kenyan music production. In a peculiar fashion that perhaps marks the male-dominated nature of the industry at the time and the potent power of trends, most practicing bands during this time featured the word ‘Boys’ in their name.

The renewed spirit of hope, industriousness, and entrepreneurship attracted not just businesspeople but also musicians and other artists from surrounding countries such as Congo, Rhodesia (present day Zimbabwe), Zambia, Uganda, South Africa and Tanganyika (present day Tanzania). As Kenyan music continued to evolve through the 1970s into the 80s, artists such as Them Mushrooms, a fashionable, all-male band of 5, were coming up.

Them Mushrooms in particular, were winning fans over as the 1980s began with a new sound called Taarab, which fused elements taken from Indian music and poetic Swahili lyrics. Later, they infused a blend of Congolese rumba, reggae, chakacha and other coastal influences into their music. Their hit song ‘Jambo Bwana’, which was released in 1982, is believed to have inspired the Disney Lion King phrase ‘Hakuna Matata’ which means ‘there are no worries’. Jambo Bwana sold over 200,000 copies between 1982 and 1987 gaining platinum certification in Kenya.

From Benga…

One of the earliest and most influential styles of Kenyan pop music is Benga, which originated in the western region of the country in the 1960s. Characterized by its measured rhythms and danceable melodies, Benga was developed by musicians who were inspired by the intersection of independence and the arrival of influences from across Africa. Benga is characterized by its use of the guitar, bass, and percussion instruments. These elements come together to create a unique and energetic sound.

Some of the most notable Benga artists include Musa Juma, Okatch Biggy, Prince July, Kamaru, Pamba Rachar, Osito Kalle, One Man Guitar, Dolla Kabarry, Richard Odongo Guya, Daniel Kamau, Ayub Ogada, whose 1992 album “En Mana Kuoyo” helped introduce the style to a wider audience, and George Ramogi, who is credited with helping to popularize Benga in the 1970s and 1980s.

…To Gengetone

In more recent years, Gengetone has emerged as a major force in Kenyan pop music, with its fast-paced, electronic sound and explicit lyrics. Gengetone draws on a range of influences, including native Kenyan music, as well as foreign genres such as reggaetone and hip hop. Some of the most popular gengetone artists include Ethic Entertainment, one of the groups that pioneered the Gengetone sound with their hit song “Lamba Lolo,” Fathermoh, Maandy, Uchungulo Family, Mbogi Genje, Ssaru, and Trio Mio.

But first…

While Benga and gengetone represent two of the most well-known styles of Kenyan pop music, they are by no means the only ones. Other popular styles include Genge, Hip-hop, Reggae, Folk music, Afrobeat, and Taarab, a form of Arabic-influenced music that originated in the coastal region of the country.

1980s-1990s

The late 1980s and early 1990s brought with them televisions and radio. It was during this time that Kenya’s second president Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi was in power. Moi was a shrewd president. He was a nepotistic, corrupt tribalist and authoritarian president who oversaw a corrupt regime that stayed in power for 24 years from 1978 until 2002.

In this period, the influence of television and radio introduced an influx of American hip-hop into the Kenyan music scene. It was during this time that groups such as Kalamashaka, Gidi Gidi Maji Maji, Mighty King Kong, an Afro-reggae singer from Western Kenya, and Ukoo Flani rose to prominence. Artists such as Eric Wainaina also came up during this time with politically charged music that stood up to the wrongdoings of the sitting government. His popular song ‘Nchi ya Kitu Kidogo’, which was released in 2001, has gotten him in trouble with the law a couple of times.

Early 2000S: The Ogopa DJs and Calif Record Era

The turn of the millennium marked the entry of Kapuka and Genge music into the scene. Helmed by artists such as Juacali, K-Rupt, E-Sir, Nameless, Kleptomaniax, Flexx, Mejja, Jimwat, Lady S, Bigpin, Patonee, Ratatat, Kaz, Nazizi, Redsan, Wyre, Avril, Marya, Deux Vultures, and the Longomba brothers, Genge and Kapuka took over the airwaves. While Genge music was mostly in Swahili and Sheng, Kapuka utilized the same as well as English and local dialects.

It was during this time in the early 2000s that recording studios Ogopa DJs and Calif Records were launched. Each unit was composed of a collection of loyal artists. Ogopa had heavy hitters such as Nameless with hits such as Ninanoki and Megaryder while Calif Records had Juacali and a little known artist going by the name Mejja who was starting to capture people’s attention.

Death of E-sir

The industry faced a terrible loss in 2003 when top Kapuka artist Issah Mmari Wangui, better known by his stage name E-Sir, died in a tragic car accident along the Nairobi-Nakuru highway while on his way back to Nairobi from a concert at Afraha Stadium in Nakuru.

Though only 21 years of age at the time of death, E-Sir had made a name for himself among the top artists in Kenya at the time with an album titled ‘Nimefika’ and numerous hits such as Mos Mos, Lyrical Tongue Twister, Kamata, Saree, Hamnitishi, and Boomba Train which featured Nameless.

As the 2000s waned, a fresh group of artists was coming up. Due to the proliferation of technology that inspired and empowered more artists to experiment with diverse sounds, Kenyan music lovers were inundated with music. From reggae music to Kapuka and folk music, every taste was catered to. This period is remembered as the golden age of Kenyan music. Among the musicians who rose to prominence during this period were Khaligraph Jones, Octopizzo, Camp Mulla, Tetu Shani, Atemi Oyungu, Chris Adwar and even rock bands such as Murfy’s Flaw and Parkinglotgrass.

Kenyan Folk Music

In Kenya, diverse communities all have their own unique forms of folk music, which is often expressed in the local language. Each community has its own distinct musical instruments and traditions, and the names for this type of music can vary. For example, the Agĩkũyũ community refers to their folk music as Mugithi, while the Luo call it Ohangla. No matter the name or the specific instruments used, folk music is an important part of the cultural identity for all communities in Kenya.

Music Instruments

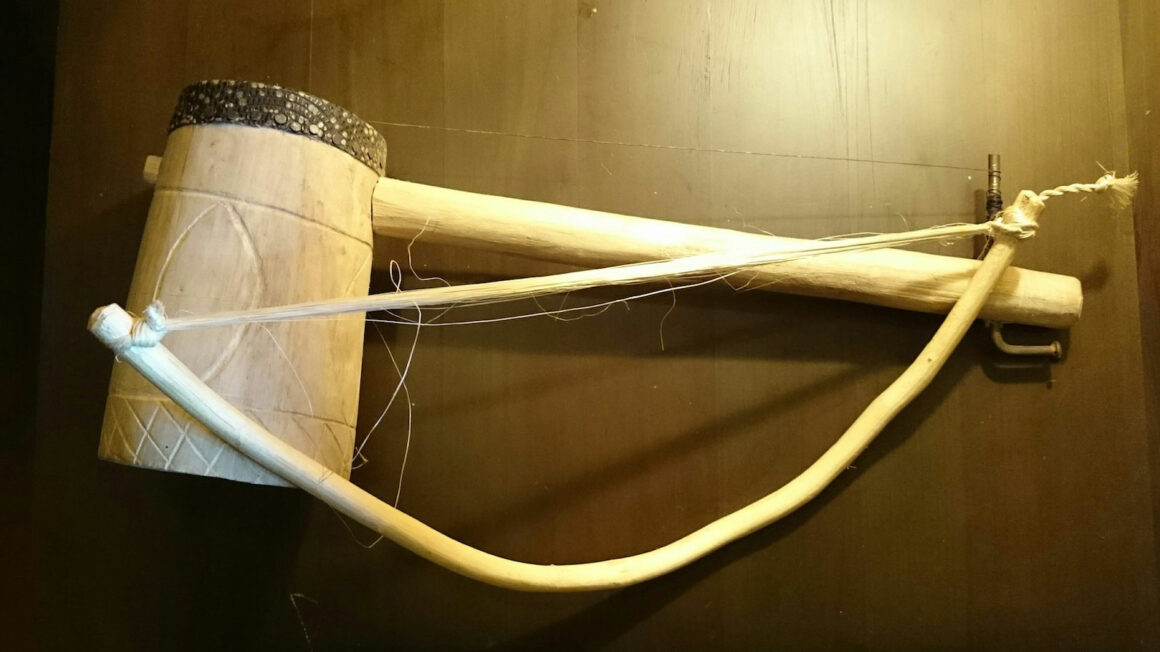

Different Kenyan communities had different instruments to accompany song and dance.

Communities from the Lake Victoria/Western Kenya region had the Siiriri (Luhya), the Adeudeu (Teso), the Litungu (Kuria and Luhya), Ekegogo (Kuria) and Ong’eng’o (Kisii).

Due to the importance placed on music in society, music instruments were handled with care and respect. The instruments were made from materials which could be sourced readily around the community’s geographical setting. This contextual factor affected which music instruments could be created. In communities whose main economic activity was dairy farming, animal skins, horns, bone and hooves could be repurposed to create music instruments. In communities that lived near forests, wood, animal skins and shells as well as metal would be made use of.

Kenya’s indigenous ınstruments include the muturiru of the Agĩkũyũ community, and the nyatiti, an 8-stringed instrument popular with the Luo community. Another popular instrument is the orutu or wandindi, which is a one-stringed vertical fiddle that was popular in the Luo and Agĩkũyũ communities.

Drums/ngoma

All over the world, humans discovered ways to make drum heads out of animal skins. The drum is a popular musical instrument in Kenya used by almost every ethnic group that practiced cattle farming, a number which includes most of them. In native Kenya, drumming was a common accompaniment to dances and rituals; it was also used as a tool for communication, celebration, mourning, and inspiration.

Burkandit

Burkandit is a string instrument used in Kalenjin music. Today, this homemade guitar of the Kalenjin people has few left who can play it well. In 1974 when US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger visited Kenya, one of the instruments that was played in his honor was the burkandit.

Kayamba

The kayamba is a percussion instrument from Kenya. A kayamba is made from reeds, seeds and wood. To play, the Kayamba is shaken sideways or up and down to create a rhythm with a soft tapering sound. The seeds or small pebbles in this raft rattle are sandwiched between two trays or rafts made of various lengths of cane tied together. The two rafts are separated by wood slats that function as the instrument’s sidewalls.

Sexist Undertones

It is not hard to see that the history of Kenyan music has leaned towards favoring men’s opinions over those held by women. This is not only evident in the mysoginistic language used in some lyrics but also in the narratives being pushed. Folk music is a big culprit here. Usually in native tongues, folk musicians get away with a lot of controversial lyrics and messaging. Many popular folk songs contain sexist language that perpetuates an outdated image of both Kenyan men and women. This language reflects attitudes that view majority of women and some groups of men negatively. Considering the hold vernacular radio still has on how information is disseminated across the Kenyan population, this is one area that needs urgent overhauling and improvement even as Kenyan music tries to steady itself on the road to acceptance at home.

Digital Music

Rapid developments in technology and changing lifestyles are transforming music. I feel fortunate that I won’t have to read about all these changes as part of some theoretical music history lesson some time in the future. With the introduction of digital music in the 1990s, internet-based music consumption has been rising steadily. More and more music listeners around the world can now share and discover new music everyday. For lovers of music, streaming began the golden age of music consumption. Up until the rise of streaming platforms like Apple Music, Mdundo, Deezer, Pandora and Spotify, music listeners had to purchase music content from individual artists, musicians and bands.

Recording Cassettes

If you wanted to jam along to the latest Them Mushrooms song, you would have to wait until the song was available on cassette or CDs. For diehard music lovers there was a hack. You could wait until a time when the song was playing on a radio station. At the time the song was playing on radio, you would hit record and ‘dub’ the song on a cassette tape. After the song played, you’d swiftly stop recording. Two things could happen if you didn’t start your cassette recording at just the right second. You would either miss the beginning of the song entirely or you would record the radio presenter’s fading voice.

Streaming: Instant Discoverability and Accessibility

Streaming provides instant access to a vast collection of music for a fraction of the cost. For approximately 500 shillings a music listener gets access to millions of songs from artists all over the world. Imagine going through a million cassette tapes to discover new music. With Spotify and the rise of streaming services, all a user needs to do to find new music is input some words into a search box on a screen. Access to a wide variety of music content on streaming platforms has created a billion dollar industry. It has also empowered musicians across the world who now have access to a global audience.

Where We Are

As the millennium’s third decade takes hold, Kenyan musicians continue to innovate around their craft, fusing the old and the new. The latest amalgamation is known as Afrobeat, a genre originating from West Africa, that takes native African rhythms and gives them a modern appeal. Afrobeat is not new. The music has existed for a while but the nomenclature seems to change at every turn. In Kenya, the genre is widely embraced and practiced by Kenyan artists such as Ayrosh, Karun, Lisa Oduor-Noah, Blinky Bill, Just-a-Band, Xenia Manasseh, Sauti Sol, Kato Change, and Winyo to name a few.

However, with the advent of western influence and the globalization of pop culture, Kenyan music has seen a decline in popularity. Many young people today are more likely to listen to Nigerian, South African, American or European artists, rather than seeking out Kenyan musicians. This shift has led to a loss of cultural identity and a disconnection from the rich musical heritage built over the decades. It will take a lot of effort from all stakeholders (artists, governments, fans, and corporate players) to turn this tide of events.

Strategies to Revitalize the Love for Kenyan Music

Among the strategies we can employ to revitalize the popularity of Kenyan music include investment in activities such as the recently ended Nairobi Festival which promote and showcase talented local musicians. We can also encourage collaboration between local artists and international musicians. Collaboration is a proven way that could help bring a fresh, global perspective to Kenyan music, while also helping to expose local artists to new audiences. At the same time, much needs to be done at the school level where investment in music education is close to non-existent, especially in public institutions.

By introducing music education programs in schools we can help to nurture the next generation of Kenyan musicians and ensure that the country has a strong pool of talent to draw from. The consecutive governments which have been power have neglected the arts and yet without government support much needed changes will be hard to achieve. By providing support for the Kenyan music industry through the development of recording studios, performance venues, and other infrastructure, the government can help create a more supportive environment for local artists.

With these steps in place, we will be on our way to regaining our sense of pride in Kenyan music and culture which will in turn help to drive demand for local music in the long term.

Muiruri Beautah

Muiruri Beautah is a Head Writer at WAKILISHA and a Marketing Manager at Peach Cars. He has created award winning work for brands such as Unilever, Diageo, SafeBoda and Safaricom Plc. He lives in Nairobi and in the hearts of children around the world.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

RIP ESir. The industry would be ahead if he didnt die

Nice read.