In the 1970s and ’80s, Nairobi’s youth found themselves caught between two worlds, one inherited, the other imagined. They were the children of independence, raised in a country still shaping its identity, yet increasingly drawn to the rhythms and visuals of a globalized culture. Televisions flickered to life in community halls, bringing in music videos, films, and images from faraway cities. Western media seeped into the city’s bloodstream, and with it came new ways of speaking, dressing, moving, and eventually, creating. A hybrid identity was forming, piece by piece, in the spaces where local and foreign collided.

What passed for street art in those early days was crude and often coded, rough tags scrawled on crumbling walls, the names of gangs etched into concrete, not for aesthetic reasons but to claim space, to mark presence, to signal power. These were declarations made in spray paint or charcoal, declarations that often spoke the language of defiance more than expression. For many, they weren’t art at all, but warnings — a visual shorthand for danger, territory, and turf wars.

Unsurprisingly, this early street art was met with hostility. To city officials and the public alike, it wasn’t creativity; it was vandalism. It carried the weight of crime, not culture. The government cracked down hard, scrubbing walls clean, criminalizing the act, and setting the tone for a long-standing tension between artists and the spaces they sought to claim. For a time, to paint on a public wall was to risk not only arrest, but also the accusation that you had nothing to say worth listening to. But even then, the urge to leave a mark and to make the city speak back never really disappeared.

The 1990s in Kenya were a decade defined by restlessness — politically, economically, and socially — and nowhere was that more palpable than in Nairobi. The country was grappling with the slow unraveling of a prolonged economic slump, while the return of multiparty politics after nearly three decades of one-party rule sent tremors through every layer of society. There was anger in the streets, tension in the air, and uncertainty about what came next. In the midst of all the chaos, a generation of artists seeking an avenue for self expression emerged.

At the time, street art and graffiti were often used interchangeably, and both were painted with the same brush of suspicion. To many, they represented defacement, a kind of visual noise that clashed with the city’s attempts at order and urban polish. Graffiti wasn’t seen as a statement or a craft; it was a nuisance, something to be scrubbed away. For the artists trying to find their footing, this made things complicated. There were few, if any, legal walls to work with, and certainly no invitations from the city.

Unlikely but Perfect Canvases

So they got creative. If the walls were off-limits, perhaps the answer wasn’t on the walls at all. It was in motion, woven into the very rhythm of Nairobi’s daily life. Matatus purpose may have been about public transportation but to pull in passengers, they needed visual flair. If your matatu wasn’t flashy, bold, and unapologetically loud, you were on the wrong side of commerce. Custom spray paint designs, meticulous airbrushing, and bold vinyl wraps turned these public transport vehicles into mobile works of art, each one crafted to catch the eye, turn heads, and stand out in the chaotic choreography of Nairobi’s streets.

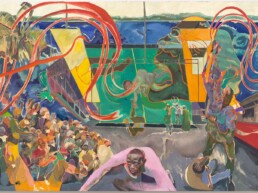

As Nairobi swelled with more people, more movement, — and more noise, its matatus grew alongside it, both in number and in size. By the early 2000s, Japanese minibuses had become the city’s dominant mode of transport, their boxy frames and broad flanks offering something the old models couldn’t: space. Not just for passengers, but for expression. The vehicles would be spray painted with all sorts of designs and images. You’d see faces of beloved musicians, both local legends and global icons, pasted beside basketball stars, footballers, the occasional beloved movie character, and more than a few nods to American hip-hop culture. Logos of brands like Pioneer, the audio gear powerhouse, became both homage and advertisement, a shared language between artist and audience. Each matatu became a collage of influence and identity, part gallery, part billboard, part moving myth. These roaming canvases traversed Nairobi every single day, seen by thousands of people. Street art had moved from the neighborhoods and been set free into the gallery called the streets. Later, this artistry that was once overlooked would become one of the most unique cultural experiences that define the city in what we now call ‘Matatu Culture’.

Words and Pictures

In time, Nairobi’s street art found not just walls, but a home, a gathering space where ideas could breathe and grow. That space was Words and Pictures, better known as WaPi. Held monthly and buzzing with energy, WaPi was a catalyst. For Kenya’s first generation of graffiti artists, it was where paths crossed, where styles evolved, and where mentorship happened in the most organic way possible, one sketch at a time. Backed by the British Council in its early days and later housed in the Sarakasi Dome in Ngara, WaPi was part of a larger vision: to nurture Africa’s creative economy by investing in its artists. But its impact reached far beyond economic strategy. It offered validation and a sense that this thing, once dismissed as vandalism, could carry weight, dignity, and purpose.

With that support came momentum. Artist collectives like Bomb Squad Crew and Graffiti Girls Kenya began to push their work deeper into the city, not just decorating it, but addressing it. Their murals didn’t shy away from the hard stuff: poverty, inequality, violence, survival. In Nairobi’s informal settlements, where public art was rare and public joy even rarer, these bursts of color and truth were welcomed. They brought vibrancy, yes, but also something deeper, a sense that someone was paying attention, that the walls could speak, and that what they said mattered.

Street Art and Social Change

What sets Nairobi’s street artists apart is not just their talent, but their nearness to the streets, to the people, and to the pulse of everyday life. They don’t create from a distance. They live the realities they paint. That proximity has given their work a rare kind of relevance, a shared emotional grammar that speaks directly to those who pass by. It’s neither abstract, nor theoretical, it’s felt. Whether addressing stigma, violence, corruption, or the quiet grind of daily survival, the art doesn’t ask for permission to be seen. It insists.

Because of its direct and in-your-face nature, street art has come to play a significant role in shaping responses to social issues in Kenya. Because it exists largely outside institutional oversight, it gives the artist an uncommon level of creative freedom, which has presented to Nairobi street artists the unique opportunity to not just react to the world around them, but to shape how their art form is understood and to reframe the conversation, to spark reflection, and maybe even hope.

Over the years we’ve witnessed various street art projects that were focused on the dynamism of Kenyan society. Some of the most striking have zeroed in on the contradictions and complexities of Kenyan society itself. Take Mavultures, for example — a 2012 campaign that took over the city’s central business district with a flurry of unauthorized murals. The images were bold, unsettling, and unmistakably clear: a visual indictment of the greed and corruption that had embedded itself deep in the country’s institutions. Painted in the dead of night, these works didn’t just critique the system, they defied it. Other projects such as the Talking Walls project in Korogocho was envisioned as a way to create a safer, more vibrant and welcoming space for the residents, with over 1 kilometer of walls painted across two streets deep in the informal settlement.

During the COVID – 19 pandemic, street art became one of the most effective ways to stem disinformation, and spread information on the prevention and management of the infectious disease. Thanks to the visually appealing nature of street art as well as the ease of understanding, street artists used their creations to educate communities on how to manage the disease appropriately.

Kenyan visual artist Msale, whose real name is Brian Musasia Wanyande, was among the artists who took to the streets of Nairobi’s informal settlements during the Covid-19 pandemic, using bold, self-explanatory murals to push back against disinformation. His work brought vital messages directly to the people, in a way that was both accessible and deeply rooted in the communities he painted in. The goal was to reach as many people as possible with clear, factual messages, the kind that could be understood at a glance while walking by. In places where tailored communication is often out of reach, these murals became a powerful tool for spreading accurate information quickly and effectively. With its evident growth in popularity, street art has become a way to not only add vibrancy by brightening up communities with color, but also as a high-visibility channel to disseminate important social messaging.

Even major corporations have begun to recognize the rising influence of Nairobi’s street art scene. BASCO Paints, one of the country’s top paint manufacturers, stepped in with a dual purpose: promoting their products while uplifting the local street art community. Through their ‘Spray for Change’ campaign, they aimed to position urban art as both a tool for neighborhood beautification and a potential source of sustainable income for emerging artists. As part of the campaign, BASCO invited artists to paint their delivery trucks turning everyday vehicles into moving pieces of art that carried the artists’ work, and their messages, to people across the country.

Bankslave

In the early 2000s, if you were young, curious, and creatively restless in Nairobi, WaPi was where you went. It wasn’t a gallery or a school, but something far more alive: a gathering place, a stage, a proving ground. WaPi was the heartbeat of Kenya’s street art movement, where pioneers like Swift9, BSQ (Bomb Squad Crew), and others opened their arms to a new generation. There was no formal curriculum, no certificates. You learned by showing up, by picking up a can, by painting alongside those who had already carved a name into the city’s walls. It worked. The proof was in the explosion of fresh voices that followed.

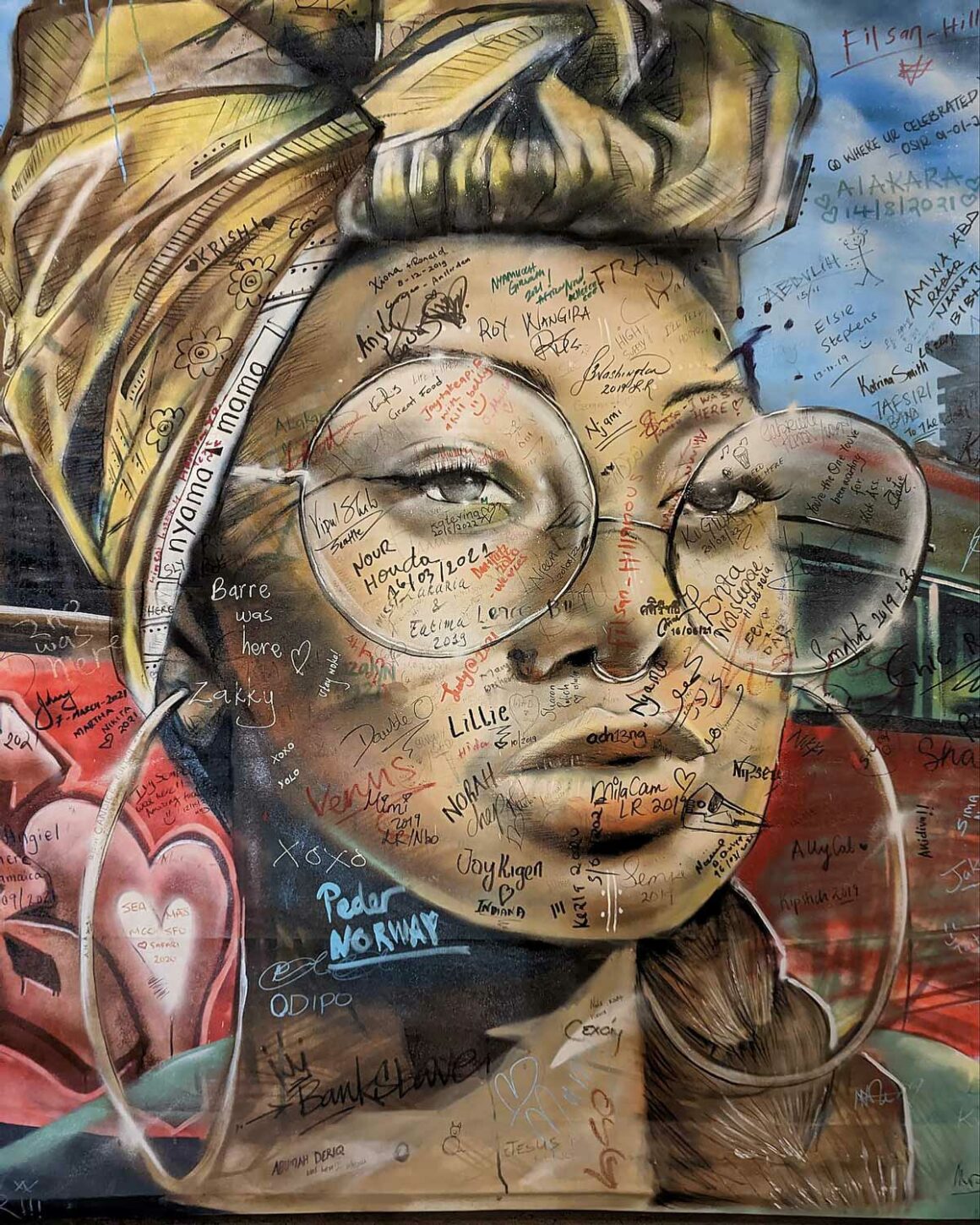

Out of that fire came names like Bankslave and Uhuru B, each with a voice, a hand, a rhythm entirely their own. You could recognize their work from across the street, not just by technique but by sensibility. They may have been murals in practice, but in reality they were declarations of presence, reflections of lived experience, and a kind of intimate conversation with the city itself.

Bankslave, in particular, became something of a legend. He approached walls with the intensity of a surgeon and the curiosity of a scientist. He would burn a hypodermic needle to melt its end, crafting it into a makeshift tool for finer spray lines, to chase a level of detail most street artists wouldn’t attempt with a can. His work stretched across the city, vast, complex, unmissable. As part of the Nairobi underground scene, He has done massive murals all over Nairobi and collaborated with groups such as 60Nozzles, Gas Crew, Spray-Uzi, and even the Ghetto-Pimps Crew from Germany. He was part of the crew behind the Kibera ‘Peace Train’ project, where trains became billboards advocating for harmony. In 2016, he took home the Hennessy ‘My Graffiti’ prize.

Swift9

Another name etched into Nairobi’s walls and its visual memory is Swift9. Describing his style as Urban Ethnikk, the Nairobi street artist blends city grit with cultural depth, creating work that feels both grounded and experimental.

Over the years, he’s lent his signature to countless graffiti and art projects, driven by a quiet determination to pull street art from the margins and into the mainstream. He doesn’t just paint for subcultures, he paints with the hope of shifting the cultural center. His win in the Spray for Change campaign was a milestone, not just for him, but for every young artist watching.

FLOSSIN MAUWANO

And then there’s Stephen Mule, though you probably know him better by his alter ego “Flossin Mauwano”. The elusive creator behind Flossin Mauwano may not spark recognition, but his work is impossible to miss. Scrawled across walls, bridges, underpasses, and road barriers throughout Nairobi, “Flossin Mauwano” is one of the city’s most persistent and haunting refrains. For Mule, it isn’t a catchphrase or a signature, it’s a memorial. Most who see the words don’t know their origin but the phrase came after Mule lost both of his parents in a road accident in 1997, he began tagging the phrase as a quiet protest, a personal act of mourning that gradually became a public reminder.

And Stephen isn’t alone in using public space for private meaning. Across Nairobi, a growing roster of street artists continue to stretch the boundaries of what graffiti can be. Bantu, mSale, Victor Mwangi aka Viktart, Chelwek, Daddo, Tyso, Esen, Wise Two, Kerosh, Shan, and Smokilah. These might not be household names, but their work resonates in alleys, on rooftops, and down the sides of buildings. Their pieces speak to anger, joy, memory, resistance, whatever the moment demands.

Meanwhile, collectives like Spray Uzi, BSQ, and Graffiti Girls Kenya, are ensuring this tradition doesn’t fade. They’re making art and they’re passing it on, teaching new members how to sketch, spray, and speak through color. In a city that sometimes forgets to listen, they remind us how to feel.

Permeating Cultural Spaces

In recent years, Nairobi’s street art has also found its way indoors onto the walls of high-end restaurants, boutique hotels, creative hubs, and curated social spaces. What was once seen as defiant and underground is now being embraced as edgy, contemporary, and culturally rich.

These murals, often commissioned, bring the energy of the streets into polished settings, creating a bridge between Nairobi’s raw creative spirit and its growing appetite for design-forward experiences. For many artists, this shift has opened up new avenues, not just for visibility and income, but for redefining where street art can live, and who gets to engage with it.

With so many artists now part of the movement, murals and graffiti have surged across Nairobi, not only in upscale spaces and cultural hubs, but also in informal settlements like Kibera, Kawangware, and Mathare, where walls have become vehicles for storytelling and social change. One striking example is the long wall leading to the Nairobi Railway Museum, transformed into a canvas for self-expression with support from the Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health. Street art has also been used to honor national icons, like the mural of Eliud Kipchoge in the heart of Nairobi’s central business district, a bold tribute to Kenyan excellence. In neighborhoods like Ngara, street art has breathed new life into historic buildings. The Ex-Telecom House, brought back to life by artist Viktart, now stands in vivid contrast to its muted surroundings.

In the end, street art in Nairobi is not just about color or protest or even beauty. It’s about the quiet, persistent human desire to leave a mark, to be seen, to be remembered, to claim a piece of the city and say, I was here, and this is what I felt. Whether sprayed onto the side of a matatu, brushed across the wall of a high-rise, or etched into the memory of a passerby, these works remind us that art doesn’t always wait for permission. Sometimes, it simply arrives and stays. Raw, urgent, and necessary.

Hafare Segelan

Hafare Segelan is a music writer, critic, curator and content creator who is the brainchild behind two popular podcasts, Surviving Nairobi and Breaking Hertz. His work has been featured on platforms such as Spotify, Apple Podcasts, The BBC and many more. You can find him on Bluesky as @hafare.bsky.social